Big tech companies, such as Facebook (Meta), trying to gain access to people’s personal information for marketing purposes is nothing new. In fact, back in 2018, Mark Zuckerberg had to testify in front of Congress to defend Facebook’s data collection practices after it was made known just how much information was being collected and what was happening to it.

Meta has gotten into more hot water of late, thanks to its data collection habits related to hospitals and patient-facing websites. But it’s likely this healthcare-related data collection doesn’t stop there.

During a recent penetration testing project, Summit uncovered a large amount of personal data that may be considered Protected Health Information (PHI) from online pharmacies being sent to data collectors including, but not limited to, Facebook. Let’s take a closer look at our findings.

Unusual Traffic

The Summit team recently was performing a routine, authorized application penetration test for a client. During testing, we noticed quite a bit of traffic from the browser destined for various social media sites and online search engines: Facebook, Twitter, Google, Bing, etc.

We analyzed these requests to determine what was in them and found that most of them had very similar contents:

- The Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) from the app we were testing, indicating that the site was collecting the links users were clicking, a tactic called click tracking

- A cookie associated with whatever social media account we were signed into, which tied the click back to us

- Referrer, which is the webpage the user clicked from, in other words, where the tracker originated

Tracking requests are generally used to track user behavior and interests so that advertisements can be more accurate and effective. They are also almost always covered under a website’s “Privacy Policy” section to protect the site from legal action in case someone does not like their user data being sent out to advertisers.

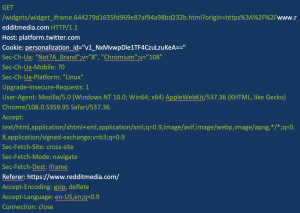

Figure 1 shows a Twitter tracker that is sent when a user clicks to visit reddit.com. All of this data is standard issue for a tracking request.

Figure 1. Example of a tracking request (white type indicates key information)

A Darker Side of Data Collection

Though the request to Twitter in Figure 1 appears to be relatively benign, closer inspection indicates it may not be. If you look at the way the request is structured, it sends the full URI. Many online pharmacies include the names of the medications in that URI. For example, the URI for CVS’s listing for Tylenol is: https://www.cvs.com/shop/tylenol-extra-strength-caplets-with-500-mg-acetaminophen-prodid-1080178.

But that “extra” information could be problematic. Because when every search query (or click) a user makes is sent to an advertiser, the data can be used to build a very real story about that user, including inferring various illnesses that s/he might be suffering from.

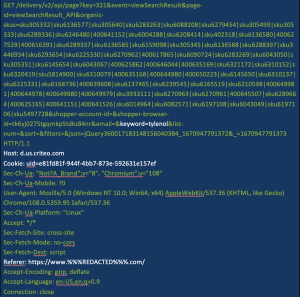

Figure 2 illustrates this scenario with what we saw during our own testing. Tracking requests generated from user clicks on a website for a large pharmacy were being sent directly to the “host” – the pharmacy’s advertising firm, a company named Criteo. The following figures use Tylenol as an example, however, actual testing used a variety of prescription medications.

Figure 2. Example of a tracking request that includes the name of a medication (white type indicates key information)

Note: information was removed from this request to protect source confidentiality.

A Fine Line

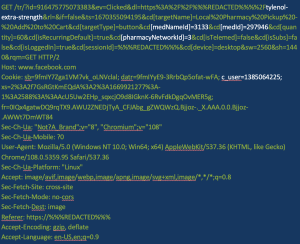

Tracking search results for medication might be a bit shady, but it is not necessarily regulated. We found that the requests being sent to Facebook, however, looked a lot like Protected Health Information (PHI) as defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

We also noted that adding a medication to the cart resulted in a request being sent to Facebook that included the medication name and ID, its price, a pharmacy network we had selected earlier, and a cookie set by Facebook to directly tie the request to our account.

Figure 3. Example of the information a tracking request sent to Facebook (white type indicates key information)

Note: information was removed from this request to protect source confidentiality.

Figure 4. Cookie status (white type indicates key information)

The “SameSite=” directive is what allows the cookie to be set in requests generated by other sites. Normally, it would be set to “SameSite=Strict” which would make it impossible for another site to call up that cookie. Because Facebook sets the cookie to “SameSite=None,” any site linking to its data collection scripts will also call that cookie, which directly ties the data to a real user.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), this collected data may be considered PHI and thus might be subject to the HIPAA Privacy Rule and/or Security Rule. According to 42 USC 1320d, section 6B, PHI is defined as individually identifiable health information that “relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual, the provision of health care to an individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual.”

The information sent to Facebook (and other data collectors) contains the names and doses of medications, which can be correlated to specific health conditions, and are included with unique identifiers to tie the information to specific individuals.

When testing this, we were also signed into Facebook to see if those advertising results came through. As a result, our Facebook instance was peppered with ads prompting the user to ask their doctor about various prescription medications. This is a potential data privacy concern as the HIPAA Privacy Rule (§ 164.508(a)(3)) has explicit requirements about the “Uses and disclosures for which an authorization is required” for marketing.

This finding prompted us to start checking other online pharmacies in the U.S. for similar traffic. Of the 92 we looked at, 14 were found to be using similar trackers. That is potentially a lot of PHI being sent to data collectors for marketing and advertising.

Even worse, these website owners may have little or no knowledge of the full extent of what is being sent out.

The Extent of the Problem

The possible scope of this finding prompted our further investigation into these requests and where they originated. The scripts that Facebook uses for this collection are all hosted on Facebook’s systems and only linked to on other sites. At the top of each one is the standard MIT license, which gives users permission to reuse code for any purpose:

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS,” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

Generally, any free-use software will have one of these licenses to protect the creator from legal action if some enterprise decides to use it and it breaks something. In Facebook’s case, it may also protect them from liability when Facebook changes the code to be more nefarious in the collection of personal data including, but not limited to, PHI.

Hypothetically, by using trackers with that disclaimer at the top, Facebook could buy a certain amount of traffic generated by a website, wait for the client to review and accept the code, and then change that code without notifying them.

As we mentioned, this type of data collection by Facebook isn’t new. In summer of 2022, Facebook’s data collection scripts were found running on a number of hospitals’ websites, sending data to Facebook on every click, including appointment-setting. A U.S. senator even became involved, demanding a response from Zuckerburg.

Several questions surround this collected data:

- Who owns it? If the data is transferred to an advertiser, like Facebook or Google, then, in theory, they own that data once it reaches their servers. Once there, they use it to advertise relevant products, in this case, medications.

- How is it being used? When Summit was doing research on this, our Facebook feed was clogged with advertisements for erectile dysfunction medication, a direct result of our test searches. A more sensitive hypothetical scenario would be if someone were searching for something like birth control medications and did not want others in the household to know. Since these requests are sent out from the user’s browser, they are also tied to their IP address. This could cause ads for birth control to show up in the feeds for everyone in that household, indirectly disclosing that information.

- Is it regulated? As far as HHS is concerned, this data may not be regulated once it reaches the data collector’s servers. HIPAA covers health plans, healthcare providers, and healthcare clearinghouses. Advertisers like Facebook and Google are none of those things, which means they are not required to follow HIPAA laws and regulations. A discussion of whether or not these data collectors are HIPAA “Business Associates” is outside the scope of this article. A remaining question is whether such data becomes PHI owned by the Covered Entity (pharmacy) by being entered by a user of its website.

Is There a Solution?

Whether you are a site owner or user, data protection is a continuous and active effort. Users can protect their data by using browser add-ons like NoScript for Firefox or Chrome that blacklist scripts from known collectors.

If you are a site owner, it is possible to manage data collection to prevent the type of scenario we describe in this blog.

- Make sure that all approved data collection scripts are hosted on your own servers. This ensures that third parties cannot make changes to those scripts without notifying you. You could also require change logs before updating the scripts.

- If you are a HIPAA Covered Entity and discover unapproved data collection scripts in your environment, investigate them according to your Incident Response Plan. If an impermissible use or disclosure of PHI has been made that compromises the security or privacy of that PHI, you should follow the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule.

- While not all data collection has nefarious undertones, your awareness of it as a site owner is key.

As you can see by our findings, penetration testing can uncover signs of data collection in your environment (along with other potentially data exposures). Because your IT and business infrastructures are continuously evolving, regular penetration testing is critical to keeping your environment safe. The right penetration testing partner can interpret the risk to your business and advise you if any action is needed based on their findings.

Summit is dedicated to keeping our clients and their businesses safe and secure through our proactive cybersecurity services. Learn more about our infrastructure penetration testing and application penetration testing capabilities.